Our house is on fire. I am here to say, our house is on fire. […] I want you to act as you would in a crisis. I want you to act as if our house is on fire. Because it is.

Greta Thunberg

At long last, the public are waking up to the threat of the climate emergency. Greta Thunberg and David Attenborough have grabbed our attention in the Western World and dragged the crisis to the forefront of global media reporting. But what can we actually do?

The IPCCs 2018 SR15 report, which was written by 91 world-leading climate scientists from 40 countries and signed off by the world’s governments, is the most up to date scientific analysis we have about the current nature of the climate crisis and how we can stop it. In the most simple terms, the SR15 gave a stark warning. We must limit global heating to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2030, or risk hitting a point of no return. This is at the stricter end of the agreement made at the 2015 Paris Climate Summit, at which countries made a non-binding committment to ensuring global heating does not exceed 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

In reality, there are very few countries who are even set to meet that target. The UK has recently set a target to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, the first in the world to do so, which is unfortunately going to be 20 years too late to prevent catastrophe. Analysis from the Climate Action Tracker suggests that there are only two countries currently set to meet the SR15’s 1.5 degree target, whilst only five more countries are on track to hit the 2 degrees target from the Paris summit.

It remains the case that a new approach to foreign and public policy is what is required to have the best chance of beating climate change. In terms of public policy, it is my view that all countries need to follow a bespoke plan for their economy. Developed countries must follow something along the lines of a Green New Deal, which in essence is made up of two parts:

- Massive investment in infrastructure and renewable energy, allowing the country to reach net-zero carbon emissions and 100% renewable sourced energy by 2030.

- A state jobs guarantee, meaning all those whose jobs are lost from removal of carbon-heavy industries are replaced with unionised state-funded jobs to build and run new infrastructure.

The UK Labour Party has recently passed a conference motion in support of this type of deal, making them the first mainstream political party in the world to do so. Based on the SR 1.5 report, meeting global net-zero by 2030 is the only real chance we have globally of combating the climate crisis and preventing temperature increases of more than 1.5 degrees. It remains to be seen whether anybody in the world will actually implement a Green New Deal. It also remains to be seen whether there are any other effective alternatives.

Countries across the world also need to form an international action plan with regards to climate repair. Climate scientists from the University of Cambridge have come up with a number of ways to ‘repair’ the climate and reverse the effects that climate change has already had. One of the most promising ideas is ‘refreezing the poles’ to restore the ice caps lost due to global heating, and prevent sea level rises. This process involves spraying seawater up tall nozzles, creating salt particles. Injecting clouds with sea salt then ‘brightens’ the clouds, spreading them out and allowing them to cool the area below. When done on a large scale, this could allow the ice retreats of the north and south pole to be reversed.

It is a common belief that the countries with the biggest impact on the global carbon footprint are developed countries, who are also considered by many to be those who will experience the worst impacts of climate change. However, this is not entirely correct. Whilst China, India and the US are the biggest global emitters of carbon dioxide, this is not the full picture. When carbon emissions are adjusted by population, the worlds ten greatest emitters are as follows:

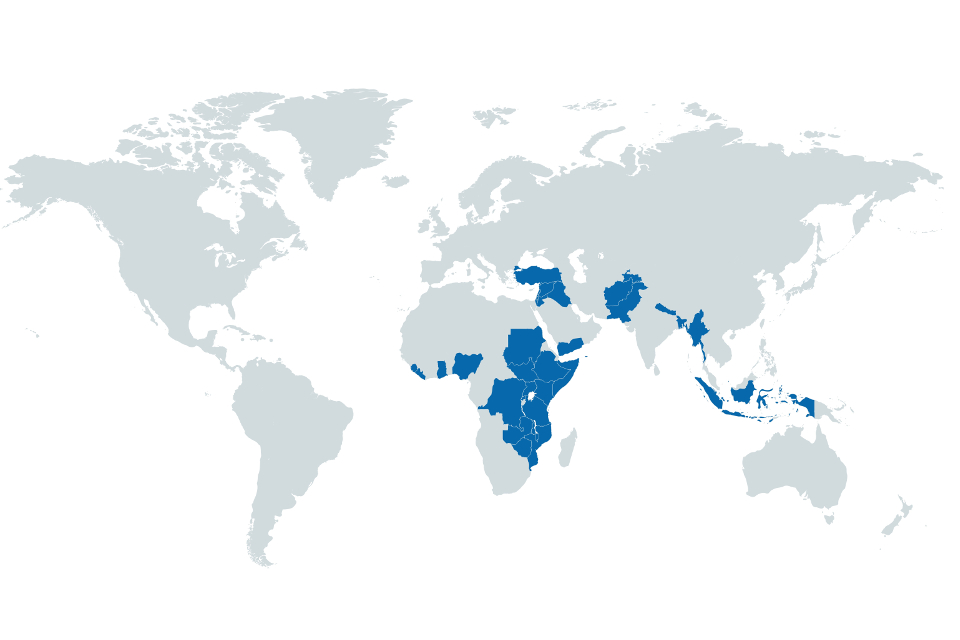

Most, but not all of these countries are part of the global north. Yet, those who will be victim to the greatest impacts will be those in the global south. An increase of 2-3 degrees above pre-industrial levels will displace up to 275 million people, who will need to be moved elsewhere (the 2015 refugee ‘crisis’ only featured 1 million people and was virtually impossible to cope with). Asian cities will be most affected, with Shanghai, Hong Kong and Osaka amongst the most affected. Across the rest of the world, cities like Alexandria, Miami, Rio de Janeiro and the Hague will be the first to fall victim to rising sea levels. As a result, climate repair and climate justice require a foreign policy approach too.

The 2015 Paris agreement was a landmark in the sense that it brought virtually all of the UN member states together in agreeing targets. However, it did not agree on solutions and the agreement reached is not binding on states. Therefore, it has little or no affect. The difficulty of cooperation, conflicting national interests and respecting individual state sovereignty makes a foreign policy approach to climate change very difficult. However, it is not impossible. Most states have vested interests in goods and raw materials created in developing nations. It is therefore in the national interest of all nation states to focus on combating climate change domestically, but also focus on aiding developing and emerging nations in combating the challenges they face.

A 2018 report from the Centre for Climate Finance & Investment at Imperial College Business School and the SOAS Department of Economics commissioned by the UNFCCC suggested that:

Increased risk from vulnerability to climate change is increasing the cost of capital and is projected to cause an additional $168 billion of debt payments over the next ten years among the most climate change vulnerable countries

It is for this reason that the richest countries must step in now to make sure climate change can be properly halted. The idea that $168bn debt is what is required of poorer countries to effectively halt climate change is going to make action impossible without the help of richer countries. The most effective foreign policy solution would be for the nations of the world to create a global climate action network, combining organisations like the IPCC into a charter which is legally binding on states. The hard work is yet to begin, but progress will be possible with global cooperation.